Fewer People and a Lot of Municipal Workers

The ratio between municipal workers and the local population is increasing in many municipalities.

Silviya Chomakova, Miroslav Hadjiiski*

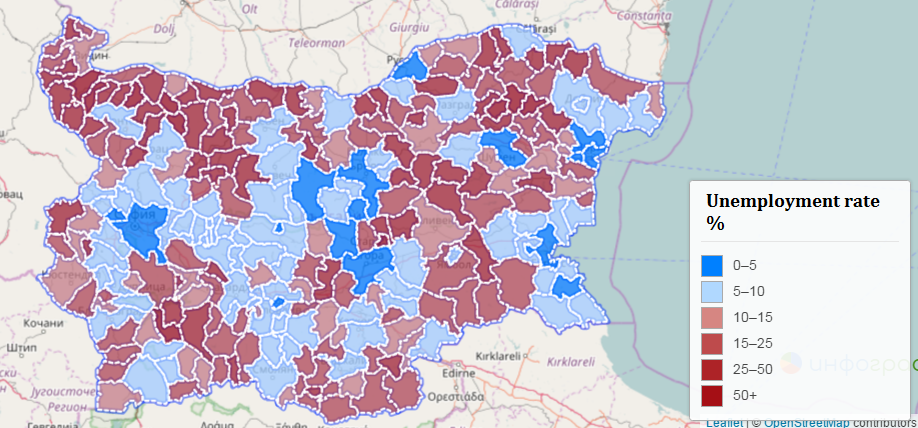

The continuous decline of the size of the population in a number of Bulgarian regions leads to more and more glaring ratios between the number of municipal workers and the people of those municipalities. This can be seen clearly on the map below, based on Ministry of Finance three-month data on the financial condition of the municipalities, including information about the number of municipal workers.

The Ministry of Finance data shows that the municipalities with the smallest administration to population ratio are Dobrich, Burgas, Sofia and Ruse – under 2 municipal employees per 1000 people. The situation is similar in other regional centers – the number of municipal employees is quite small relative to the total population.

This is quite different in the smaller municipalities, where we can see up to 10 times higher municipal employees to the total population ratios at times. A good example is Trekliano municipality in the region of Kyustendil, where there are 35 municipal workers and only 889 people. The municipalities of Boinica (1143 people), Kovachevtsi (1760) and Makresh (1438) are similar – there there are more than 20 administration employees per 1000 people.

Two of the aforementioned municipalities, Boinica and Makresh, are located in Vidin region, where a big ratio of administration workers compared to the total population can also be observed in the municipalities of Gramada, Novo selo and Kula. This data shows that even though a territorial-administrative reform is currently not on the agenda, it simply cannot be avoided in the future, especially if the current rights and obligations of the municiplaties remain the same or even increase. There are some municipalities where the local administration is among the largest employers – a fact that, alongside with the issues of public spending effectiveness, raises major concerns about the political processes on local level.

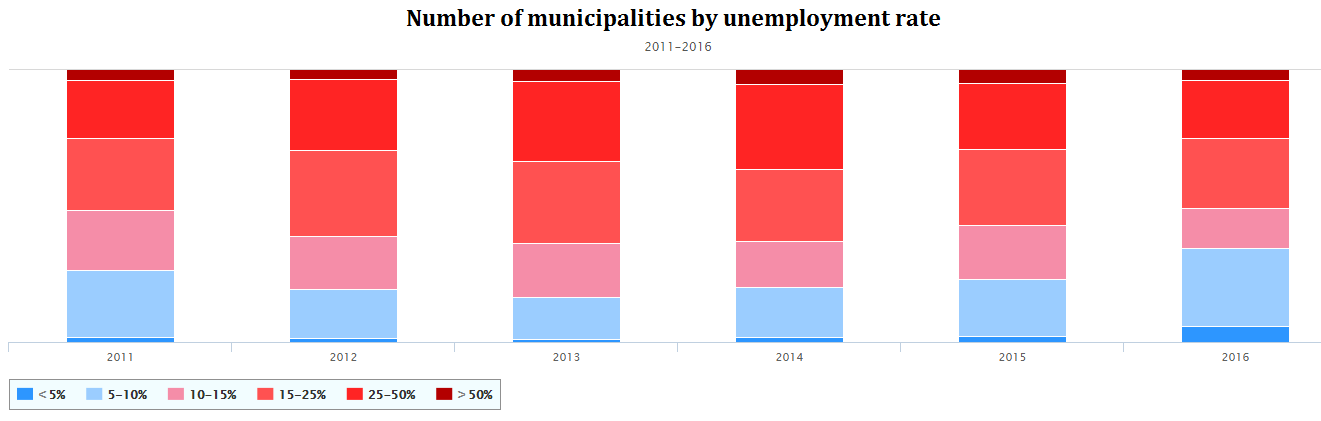

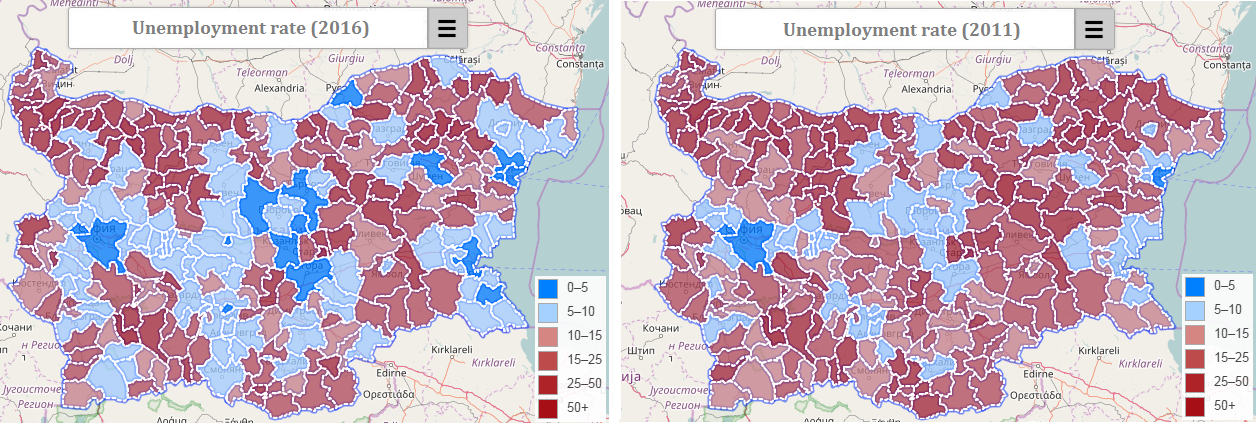

Major differences in the ratio between municipal workers and the local population can also be observed on the district level. Here we must point out that the data is from two different sources – the official yearly reports of the municipalities (published in 2010 and 2014) and Ministry of Finance data(form 2016), and for this reason they individual data points may not be fully comparable.

There is a declining number of municipal employees per 1000 people in some parts of the country. Dobrich is one of the best examples for this trend, since in 2014 there were 7,18 municipal employees per 1000 people, while in 2016 their number declined to 4,35 per thousand. A similar trend can also be observed in other regions such as Plovdiv, Yambol, Haskovo and Gabrovo. The overall population size and the number of municipal employees here are linked proportionally – as the size of the population declines, so does the number of municipal employees in those regions.

The opposite trend is observed in the regions of Kardjali, Varna, Kyustendil, Vratsa, Pernik and Silistra. The rise in the number municipal workers in Kardjali can be seen clearly in the table (in 2014 there were 6,72 administration employees per 1000 people, whereas in 2016 the number rises to 7,76). This drastic increase in this ratio is the result of the decline of the size of the overall population, combined with an increase in the number of municipal workers keeps; this is true for Kardjali and all of the aforementioned regions.

Ceteris paribus, the declining population of Bulgaria should result in a decline in the size of the administration, especially in the regions where there is a steady trend of negative natural and mechanical growth. Turning the municipal administrations into the main employer in those regions leads to a number of problems, especially in terms of the functioning of local democracy. In addition, the vicinity of small municipalities with high municipal employees to population ratios (such as Trekliano) and big municipalities with low ratio (such as Kyustendil), once more points to the need of a territorial-administrative reform.

November 29th, 2016 | 11:00 - 12:00

November 29th, 2016 | 11:00 - 12:00