The Share of Dropouts Is a Growing Concern

The reasons for dropping out of school are different at various education levels.

The beginning of the school year is a good time to comment on one of the important problems of the Bulgarian education system - dropout rates, which until recently were rather outside the focus of the public debate on the sector's policy. Here we will look at several aspects of this problem - its territorial peculiarities by districts and municipalities, its distribution in different levels of school education and the possible reasons behind it.

Source: NSI

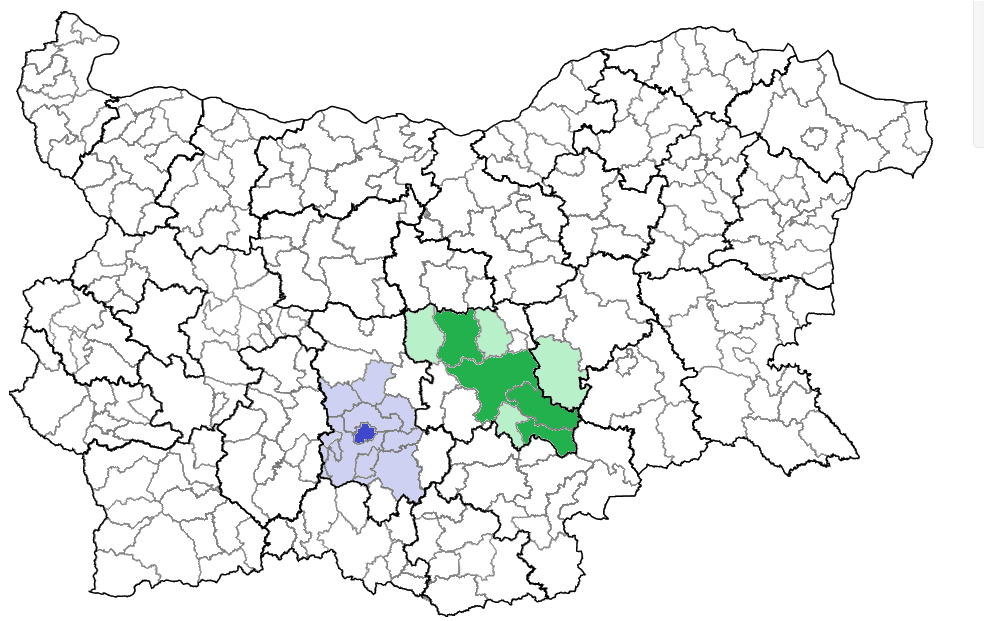

NSI’s municipal level data on dropouts in the 2015/16 school year only refers to early dropouts and therefore covers only students who left school before the eighth grade. Thus the dropout rate presented on the map underestimates the real dimensions of the phenomenon by just under one third, but still allows comparisons between different parts of the country. The breakdown by municipalities shows that in most of them (101) the share of school leavers is less than 2%. There are, however, several "clusters" of municipalities where the the problem is significantly more severe - several small municipalities around Vidin and Vratsa, almost all municipalities in the Dobrich district, two municipalities south of Burgas and several near Ruse, Plovdiv and Stara Zagora, where the rate exceeds 7-8% of the students. Fewer separate municipalities - Tran, Letnitsa, Venetz, Hitrino, Kostinbrod are also among the worst performers.

It is worth noting that in almost all of South-West Bulgaria the dropout rate is very low. A visible factor that determines the share of school dropouts is the size of the municipality - large municipalities and district centers achieve better results than small municipalities. Curious exceptions to this rule are Pazardjik, where the share of early dropouts is 5.6%, as well as Nova Zagora, where in 2016 it reaches 7.3%. The best result is achieved by the Municipality of Madan, where the dropout rate is 0.1% and the worst performer is the municipality of Nikolaevo (13.9%).

Source: NSI

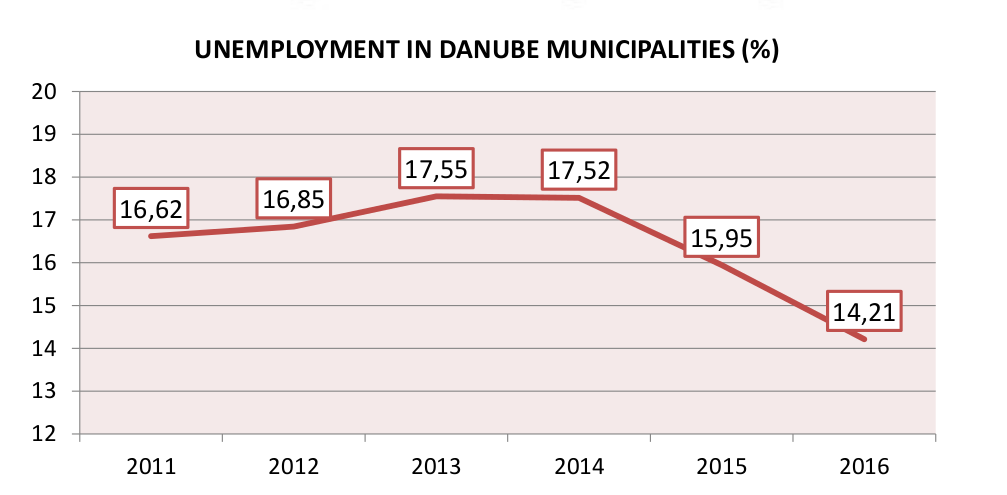

Since presenting dynamics at the municipal level would be difficult, the chart above shows district level data. Despite commitments and policies aimed at reducing and eliminating early school leaving, there is no visible improvement in most districts. To the contrary – in most districts dropout rates have either been increasing, or have remained unchanged.

The distribution of dropouts between the three levels of school education allows us to determine the level of education in which the risk of dropping out is the highest. In 2015/16, most of them dropped out during the four years between the fifth and the eighth grade, which is also true for previous years. It is thus obvious that the lower secondary education level is the one in which the educational system achieves its biggest failure to keep the students. Primary and secondary education, on the other hand, have a relatively equal dropout rate.

The reasons for the large share of dropouts vary across the different educational stages. While in the early stages the main reason is “departure abroad”, "family reasons" and reluctance to attend school (which is virtually absent in primary education) are becoming more and more important during high school. The review of school dropout data does not paint a particularly positive picture. Although the problem has not become more severe in recent years, it can not be said that policies aimed at solving it have achieved any success.