Round Table Discussion "The Economic Centers in Bulgaria"

On January 18, 2018, the Institute for Market Economics (IME) will present its pilot study "Economic Centers in Bulgaria".

On January 18, 2018, the Institute for Market Economics (IME) will present its pilot study "Economic Centers in Bulgaria".

January 18, 2018, 10:00 to 12:00

French Institute | P. R. Slaveykov Sq. № 3

On January 18, 2018, the Institute for Market Economics (IME) will present its pilot study "Economic Centers in Bulgaria". The study is the first of its kind and will be presented at a round table with representatives of the executive and legislative authorities, business, academic circles, civil society and the media.

In 2017 IME set itself the goal of determening the boundaries of the economic centers in the country. Our ambition was to "overcome" the administrative-territorial division of the districts and regions and to draw new internal borders in the country based entirely on natural economic processes. As a result of these efforts, we have identified both the strongest nuclei of the national economy, as well as their adjacent periphery of municipalities.

|

10:00-10:30 |

Welcome coffee |

|

10:30-11:15 |

Presentation of the study "Economic Centers in Bulgaria" |

|

11:15-12:00 |

Discussion |

Please confirm your presence by 15 January to Vessela Dobrinova, 02/952 62 66, vessela@ime.bg.

We are expecting you!

The IME team

The IME proposed that 1/5th of all income tax revenues should be transferred to municipalities.

During the presentation of "Regional Profiles 2017", the IME proposed the redirection of 1/5 of income taxation revenues to municipalities. This is a proposal that the IME has also put forward in previous periods, a detailed version of which is available in the article „Fiscal Policy and Regional Development: Recommendations for Changes in Income Taxation” (2014). At the beginning of this year, we also pointed the attention at the trend of rising local taxes - "Municipalities Will Continue Raising Taxes Unless We Change the Model " (2017).

IME's proposal is that income taxes should continue to be collected in the same way - by the NRA, which will afterwards automatically transfer 1/5 of the proceeds to municipalities following the principle "money follows the ID card" – i.e. revenues end up where the person is registered. Our calculations indicate that this resource would amount to BGN 634 million in 2018, which means almost doubling the tax revenues of municipalities. This reform would greatly improve the state of municipal budgets, creating opportunities for both repayment of debts and new capital expenditures. There will also create incentives for local authorities to work for more investment, higher employment and wages.

The map below shoes how these BGN 634 million would be allocated to individual municipalities. IME’s calculations are based on the number of employees and wage levels in each municipality, with only two municipalities missing. Such an account is most likely made at the NRA but is not currently publicly available. The overall conclusion is that all municipalities would benefit from the reform, while those who concentrate more economic activity (higher employment and higher wages) will get a resource that would make them much more independent than the central government.

By how much would the budget of Bulgarian municipalities increase if they receive 1/5 of income tax revenues? (2018 projection, BGN)

Source: NSI, IME calculations

IME presented the new edition of "Regional Profiles; Indicators of Development"

The English edition of the study will be available in February 2017.

November 28th2017 11:00 - 12:00 | BTA Pressclub

On Tuesday, November 28th at 11 o’clock the Institute for Market Economics (IME) will present the key findings of this year’s edition of the “Regional Profiles: Indicators of Development” study. The regional profiles are a unique study of the socio-economic conditions and development of the regions in Bulgaria, compiled by the IME for the sixth consecutive year, allowing for the underlining of long-term processes on the regional level.

The English version of the study will be available in December 2017.

This year, the presentation will focus on the following topics:

The findings will be presented by:

The complete analyses, data and other materials included in the study will be uploaded on the project’s website.

For more information: Vessela Dobrinova (02/952 62 66, vessela@ime.bg)

On Tuesday, November 28th at 11 o’clock the Institute for Market Economics (IME) will present the key findings of this year’s edition of the “Regional Profiles: Indicators of Development” study.

November 28th2017 11:00 - 12:00 | BTA Pressclub

On Tuesday, November 28th at 11 o’clock the Institute for Market Economics (IME) will present the key findings of this year’s edition of the “Regional Profiles: Indicators of Development” study. The regional profiles are a unique study of the socio-economic conditions and development of the regions in Bulgaria, compiled by the IME for the sixth consecutive year, allowing for the underlining of long-term processes on the regional level.

The English version of the study will be available in December 2017.

This year, the presentation will focus on the following topics:

The findings will be presented by:

The complete analyses, data and other materials included in the study will be uploaded on the project’s website.

For more information: Vessela Dobrinova (02/952 62 66, vessela@ime.bg)

A review of EA data shows that there is a high relative share of vacancies, which offer a minimum wage (29.3%).

The analysis of the open data of the Employment Agency (EA) largely confirms some already established trends in the labor market. As of 9 November 2017:

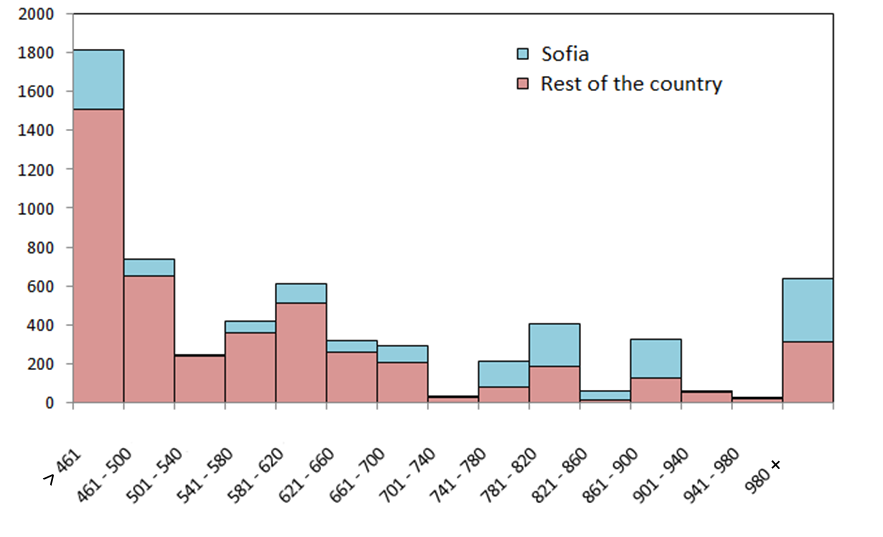

Despite Smolyan‘s current top ranking in terms of average wages proposed, the capital continues to be the district concentrating a large part of the vacancies both in general (26.5%) and in the high-paying job offers. Sofia generates only 18% of the minimum wage jobs and 51% of those offering over 1000 BGN. More than half of the job posts in the capital are for over BGN 750 pay.

Number of vacancies depending on the salary offered (as of November9th, 2017)

Source: EA, IME calculations

IMPORTANT : All calculations in this material take into account only job posts that contain information about the proposed remuneration and workday duration. This implies some conditionality in the interpretation of data for regions where, for various reasons, labor offices/agencies do not collect/publish comprehensive vacancy information. As of November 9, 2017, 56% of job posts containing 52% of all vacancies did not contain information regarding the offered payorworkday duration. Although there has been some improvement over previous periods (when this share was close to 70%), the lack of this information hampers not only the analysis but also the process of job mediation – linking job seekers with employers.

Once again, the review of EA data shows the high relative share of vacancies in the country, which offer a minimum wage (29.3%) . If we set the threshold not at BGN 460, but rather and at the expected level from 1 January 2018 (BGN 510), this share jumps to as much as 42%. Simply put, this is the share of job vacancies in labor offices that can be affected by the planned lifting of the minimum wage.

Of the 90 municipalities for which there are comprehensive vacancy data available, there are 7 where the average wage offered is equal to the minimum wage (Veliki Preslav, Gotse Delchev, Kubrat, Pavlikeni, Ruen, Krumovgrad and Kula) and in another 17 it is below the expected level of the minimum wage as of January 1, 2018 (BGN 510).

In many of the poorer areas of the country, there is also an extremely low share of jobs for which both pay and working time are declared. It will not be surprising if it turns out that many of the "hidden" conditions for starting work are hidden for good reasons (such as lower than minimum wage or unwillingness to disclose the actual one). Given that only two months later, 42% of currently available jobs will have to be adjusted to the new minimum wage, these problems may get worse.

Share of job vacancies which contain information about the offered payment (%)

Source: EA, IME calculations

The reasons for dropping out of school are different at various education levels.

The beginning of the school year is a good time to comment on one of the important problems of the Bulgarian education system - dropout rates, which until recently were rather outside the focus of the public debate on the sector's policy. Here we will look at several aspects of this problem - its territorial peculiarities by districts and municipalities, its distribution in different levels of school education and the possible reasons behind it.

Source: NSI

NSI’s municipal level data on dropouts in the 2015/16 school year only refers to early dropouts and therefore covers only students who left school before the eighth grade. Thus the dropout rate presented on the map underestimates the real dimensions of the phenomenon by just under one third, but still allows comparisons between different parts of the country. The breakdown by municipalities shows that in most of them (101) the share of school leavers is less than 2%. There are, however, several "clusters" of municipalities where the the problem is significantly more severe - several small municipalities around Vidin and Vratsa, almost all municipalities in the Dobrich district, two municipalities south of Burgas and several near Ruse, Plovdiv and Stara Zagora, where the rate exceeds 7-8% of the students. Fewer separate municipalities - Tran, Letnitsa, Venetz, Hitrino, Kostinbrod are also among the worst performers.

It is worth noting that in almost all of South-West Bulgaria the dropout rate is very low. A visible factor that determines the share of school dropouts is the size of the municipality - large municipalities and district centers achieve better results than small municipalities. Curious exceptions to this rule are Pazardjik, where the share of early dropouts is 5.6%, as well as Nova Zagora, where in 2016 it reaches 7.3%. The best result is achieved by the Municipality of Madan, where the dropout rate is 0.1% and the worst performer is the municipality of Nikolaevo (13.9%).

Source: NSI

Since presenting dynamics at the municipal level would be difficult, the chart above shows district level data. Despite commitments and policies aimed at reducing and eliminating early school leaving, there is no visible improvement in most districts. To the contrary – in most districts dropout rates have either been increasing, or have remained unchanged.

The distribution of dropouts between the three levels of school education allows us to determine the level of education in which the risk of dropping out is the highest. In 2015/16, most of them dropped out during the four years between the fifth and the eighth grade, which is also true for previous years. It is thus obvious that the lower secondary education level is the one in which the educational system achieves its biggest failure to keep the students. Primary and secondary education, on the other hand, have a relatively equal dropout rate.

The reasons for the large share of dropouts vary across the different educational stages. While in the early stages the main reason is “departure abroad”, "family reasons" and reluctance to attend school (which is virtually absent in primary education) are becoming more and more important during high school. The review of school dropout data does not paint a particularly positive picture. Although the problem has not become more severe in recent years, it can not be said that policies aimed at solving it have achieved any success.

Stara Zagora is already working on establishing its own industrial zone - "Zagore"

Stara Zagora is already working on the establishment of “Zagore” Industrial Zone. The latter is not a surprise, as it has been discussed intensely over the past year. Undoubtedly, this step is provoked by the positive development of Plovdiv, which is to a large extent the result of the positioning of “Thrace” Economic Zone as a leading investment destination in Bulgaria. The latter is particularly important – any efforts on the establishment of an industrial area should always be targeted at creating suitable conditions and positioning a settlement as an investment destination.

Plovdiv's positive experience in developing the “Thrace” Economic Zone has created expectations both for its expansion and the replication of this model in other regions. In terms of enlargement, for example, “Thrace” Economic Zone has already included the municipalities of Haskovo and Dimitrovgrad. Recently, in a presentation in the municipality of Haskovo, we answered the question why this was expected to happen. While Haskovo can hardly be positioned as a separate center (investment destination), it is relatively easy to include it in the portfolio of “Thrace” Economic Zone and to aquire certain investments that correspond to the profile of the local workforce.

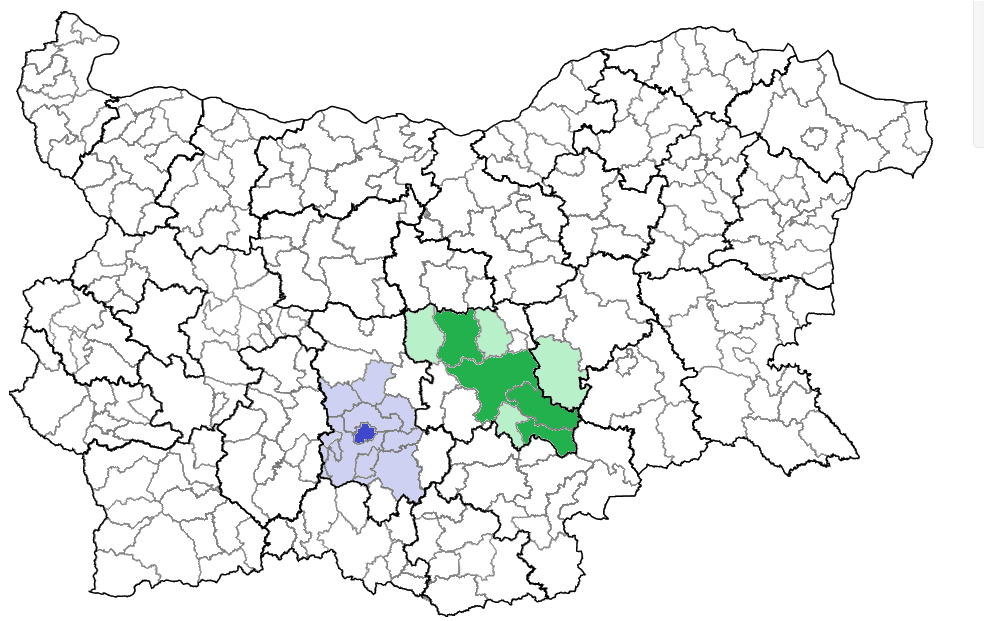

Thus the first comprehensive attempt to replicate the model of Plovdiv will happen in Stara Zagora. The socio-economic profile of Stara Zagora virtually implies the decision to differentiate it as a separate investment destination and not simply as an "attachment" to the “Thrace” Economic Zone. Let's take a look at what these areas would look like, by presenting a general overview of the Plovdiv and Stara Zagora economic areas.

Our work on highlighting and analyzing the economic centers in Bulgaria allows us to separate the two economic areas by presenting the relevant center for the area and its periphery. Under “periphery”, we count these municipalities that daily “send” 10% of their workforce to the center.

The economic area of Plovdiv consists of the natural center (the municipality of Plovdiv) and its periphery includes the municipalities of Asenovgrad, Kaloyanovo, Krichim, Kuklen, Maritsa, Perushtitsa, Plovdiv, Rakovski, Rodopi, Sadovo, Saedinenie and Stamboliiski. Each of these municipalities sends daily more than 10% of its workers to the municipality of Plovdiv.

The economic area of Stara Zagora is a bit more complicated to differentiate. The reason is that there are several centers and fewer peripheral municipalities. As centers we can point out the municipalities of Stara Zagora, Kazanlak, Radnevo and Galabovo, while the municipalities of Opan, Maglizh, Pavel Banya and Nova Zagora are peripheral. It is interesting to note that Nova Zagora (because of daily labor migration to the municipality of Radnevo) is also entering this wide economic area, although it is part of another district (Sliven).

Map: The Economic Areas of Plovdiv and Stara Zagora

Source: IME

* In this map the municipalities of Haskovo and Dimitrovgrad are not included in the economic area of Plovdiv.

Although it looks like the area of Stara Zagora is similar in size, the socio-economic indicators show that Plovdiv is almost twice as significant. The population in the Plovdiv area is 568 thousand people (of which 343 thousand in the municipality of Plovdiv), while in the wide area of Stara Zagora live 322 thousand people (158 thousand in the municipality of Stara Zagora).

Table: Comparing The Economic Areas of Plovdiv and Stara Zagora

|

Plovdiv |

Stara Zagora |

|

|

Population (2015, thousand) |

568 |

322 |

|

Production output (2015, billion BGN) |

13,1 |

7,1 |

|

Investment in fixed tangible assets (2015, million BGN) |

1594 |

840 |

|

FDI in non-financial enterprizes (cumulative as of 31.12.2015, million BGN) |

1429 |

1082 |

|

Manufacturing employment (2015, thousand) |

60,6 |

32,2 |

|

Average monthly gross salary (2015, BGN) |

771 |

786 |

Source: IME

* In this map the municipalities of Haskovo and Dimitrovgrad are not included in the economic area of Plovdiv.

The difference in output also corresponds to their scale - BGN 13.1 billion in the Plovdiv economic area and BGN 7.1 billion in Stara Zagora, the latter being relatively evenly distributed in the four centers of the zone (the municipalities of Stara Zagora, Kazanlak, Radnevo and Galabovo). Cummulative FDI amounted to BGN 1.4 billion in the Plovdiv area and BGN 1.1 billion in Stara Zagora. The relatively smaller difference in FDI compared to the scale of production is due to the accumulated foreign capital in Galabovo (BGN 756 million of the BGN 1.1 billion in question). The expenditures on FTA, which also account for local investments and are largely influenced by EU funds, reveal a difference similar to that in output - BGN 1.6 billion in the Plovdiv area compared to BGN 840 million in Stara Zagora.

A serious difference between the two areas is the greater employment in the mining industry in Stara Zagora – including over 5.5 thousand employed in the mining industry in the municipality of Radnevo. The employees in manufacturing are 61 thousand in the Plovdiv area (34 thousand in the municipality of Plovdiv) and 32 thousand in the Stara Zagora area (13.5 thousand in Stara Zagora). In terms of the ICT sector, the differences are even greater - 3 200 hired in the Plovdiv area compared to 650 in Stara Zagora.

Stara Zagora, however, does not give way to Plovdiv in terms of average wages. On the contrary, if the considerably higher salaries in the municipalities of Galabovo and Radnevo are taken into account, the average salary in Stara Zagora (BGN 786 per month) exceeds that in the Plovdiv area (BGN 771 per month). This should also be taken into account when positioning Stara Zagora as an investment destination, which at times may compete with Plovdiv to attract one or another foreign investor.

The main conclusions of this review are the following:

All that has been said so far only outlines the basic features of the two zones. In the coming months the IME will present an in-depth study of all economic zones in the country.

Sofia for another year breaks away from other regions in economic development 16.02.2026

In 2024, Sofia continues to stand out more and more clearly in its economic development from the other...

Bansko on the eve of the Winter Games 09.02.2026

Today is the official opening of the 25th Winter Olympic Games in Milano Cortina. Two decades after the...

Disability pensions are affected by demographics, but also by unemployment by region 06.02.2026

NSSI data show that there are over half a million people receiving disability pensions. However, the regional...

Economic and social development of the districts over the last decade 12.01.2026

The IME Regional Profiles study has been tracking the economic and social development of regions in Bulgaria...