Fiscal Policy and Regional Development: Recommendations for Income Tax Decentralization

In recent years, we have repeatedly emphasised on the state of local finances in Bulgaria, and also on the ongoing local tax policy. We publicised the thematic analysis Local Tax Policy in the previous edition of Regional Profiles: Indicators of Development, which discloses some of the main challenges before local finances:

- High dependability of local budgets on government transfers. Central budget transfers continue to exceed own-source revenues. Delegation of certain tax powers from the government to local authorities has been quite insufficient in recent years, and did not change the general framework.

- Highly restricted rate of tax revenues to municipalities. Own-source revenues are mostly non-tax revenues, i.e. ones that are in exchange of specific administrative services, and that do not give freedom in conducting tax policy. This reduces the opportunities for public investments, and also for covering contingencies.

- The lack of connection between tax revenues and the economic development of a territory. Municipalities’ tax revenues, which generally constitute one fifth of municipal budgets, are generated mainly from property taxes, i.e. they do not have a direct bearing on incomes and profits in the municipality. Only resort municipalities represent an exception to this rule, and have a higher degree of financial independence.

- An increased dependence of municipalities on EU funds. Capital expenditure of local budgets is largely financed by EU funds. Thus, public investments detach even more from the local economy and become an administrative process.

- Lack of flexibility that causes a shortage of funds even at the slightest shock. During the crisis years, deficits loomed over local budgets and debts quickly piled up (more than 900 million BGN as at the end of 2013). In recent years, there have also been a number of examples of municipalities with frozen accounts, or municipalities that have shut down for several days or weeks due to their inability to meet their operating expenses.

All of the above outlines a bleak background that explains many of the regional development’s shortcomings, starting from the deepening discrepancies in a socioeconomic respect between the centre and the periphery, which have been again brought to the fore in this edition of Regional Profiles: Indicators of Development. Despite the fact that these problems are well-known, the events from the past year have urged us to consider two visiosns for regional development: the vision of administrative development or the vision of development that rests on financial independence. We will not only be critically analysing the first approach, but will also be presenting real steps for changes in the tax structure that will enable the second one.

Regional development – investments and EU funds

The relation between fiscal policy and regional development does not simply end with the availability of public resources and their expending thereof. The structure of local finances and also the incentives for local authorities, which arise from this structure, are key to the development. The current reality is that local authorities have no incentives (at least from a financial point of view) to attract investments in the relevant municipalities and not to hinder economic activity and entrepreneurship. In the current situation, a new investor in any municipality would not bring in new funds; even, on the contrary, it could cause public expenses on the corresponding infrastructure. The national budget automatically reaps any benefit, in terms of the budget, from any new investment or new job.

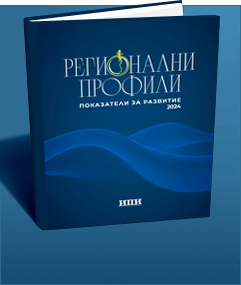

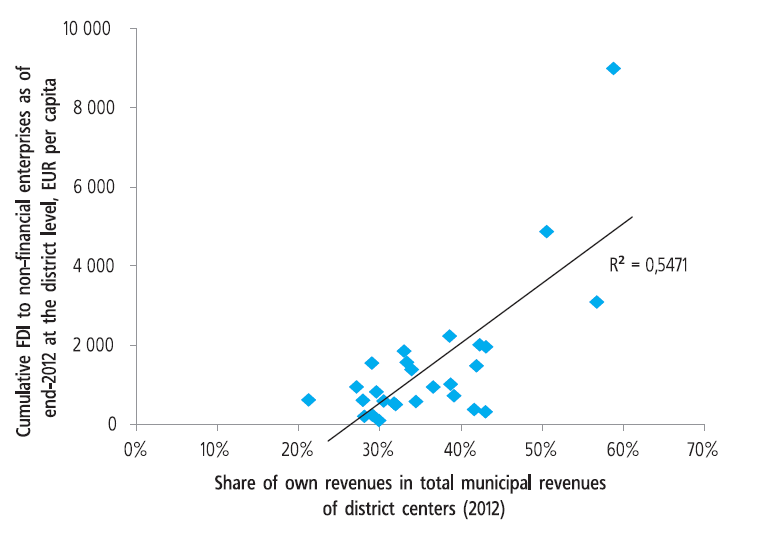

This practically means that the lack of financial independence entails poor interest in attracting investments and in removing hindrances before local entrepreneurs. We could try to verify this assertion by comparing the NSI’s data on foreign direct investments (cumulative) per district, and also the data on the acquisition of fixed tangible assets, to the data of the Ministry of Finance on the share of own-source revenues in total revenues in the budget of municipalities and district centres. Despite the insufficient accuracy of such a comparison, it is the best possible because there are no data on foreign direct investments on local level. While taking into consideration that district centres strongly affect the economies of the respective districts, we could largely rely on the results. And the results are exactly the expected ones: the correlation between the financial independence of municipalities and district centres and foreign direct investments, or the expenditure on the acquisition of fixed tangible assets in the district, is obvious. Sofia District, where there is no district centre, has been excluded in this instance; a high inflow of investments has been observed due to the proximity to the capital city.

Figure 1: FDI and financial independence of district centers

Source: NSI, MoF, IME

Figure 2: Expenditure on the acquisition of fixed tangible assets and financial independence of district centers

Source: NSI, MoF, IME

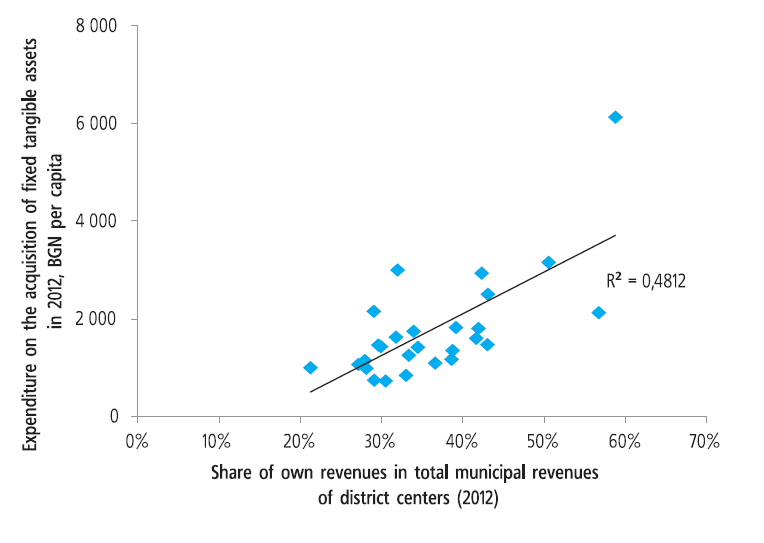

Though we cannot assert that the financial independence has brought investors (or vice versa), we cannot neglect the presence of a correlation between the two, and also that the municipalities featuring higher financial independence are in principle more active in their attempts to position themselves as an investment destination. Moreover, there is no similar positive correlation between financial independence and the utilization of EU funds. The lack of correlation is clear if the data of the Ministry of Finance on the share of own revenues in proportion to total revenues in the budget of district centres, and the data on EU funds utilised by the relevant district centres are used. Actually, if there is a hint of any correlation, it is rather negative. In other words, the utilisation of EU funds is largely related to the administrative capacity of municipalities, and has no direct relation to their financial independence.

Figure 3: Utilization of EU funds and financial independence of district centers

Source: MoF, IME

The data presented above demonstrate that there is correlation between the financial independence and investments (foreign or domestic); while there is not any between the financial independence and the utilisation of EU funds. The financial independence per se is not a panacea (there are lots of other factors); it directly affects the incentives and the activities of municipalities for attracting investments and for removing obstacles before local entrepreneurs. Observations from recent years have also implied that while all municipalities work in reality for utilising EU funds (with varying degrees of success), a very limited number of them could be commended for real activities for attracting foreign investors. The lack of a strong correlation between investments made and the inflow of new funds in municipal budgets compels local administrations to focus on EU funds and the so called utilisation, which does not always mean achieving real results.

Administrative development of districts

The problems of local budgets in recent years have led to the emergence of a new administrative mechanism for public investments in districts, which, however, has relied again on centralised funds management. The so called ‘Growth and Sustainable Development of Districts’ Public Investment Programme, the aim of which is predominantly to fund local projects, i.e. to provide funds for investing on local level, was initiated in 2013. The real implementation of this ‘programme’ only consolidated the negative attitudes toward the idea regions to develop via a new form of public transfers and subsidies.

Though ‘investment programme’ or ‘regional fund’ have been frequently used, it is important to note that neither was any fund created, nor any programme has been made available. The planned 500 million BGN for regional development were simply provided for in the budget (in the so called ‘reserve for contingencies and urgent expenses’). This actually is an item that is being blindly voted by Parliament, but subsequently is being expended via resolutions of the government. In other words, this is an item that allows the government to spend certain funds at its discretion, without any explicit sanction of Parliament.

The government has quickly allocated the 500 million BGN in question as early as the beginning of the year, and a detailed review of funded projects clearly demonstrates that money has been largely allocated on political basis[1]. Comparing the projects, applied for and won ones, and the political affiliation of mayors unambiguously supports such an assertion. The exceptionally short deadlines in which projects were verified, and the subsequent information that a number of municipalities had not been ready to start implementing their projects, are added to this. All of this once again confirms that such a practice of administrative and political allocation of funds is inherently wicked.

In this instance, even if we avoid some faults of the investment programme in question (the lack of any fund and regulations regarding work, for example), the very idea municipalities to develop via a new centralised means will only deepen the structural problems before local finances. Generally, such a practice would worsen the problems specified at the beginning of this text – bigger dependability of local finances on the state, and also an additional disruption of an even loose connection between municipal budgets and the local economy.

Local democracy and legitimacy

The economic and financial issues before municipalities could also be regarded in a wider context that is related to the political life in Bulgaria. Domestic democracy has a number of flaws that are especially distinguishable on local level. In purely political terms, a strong domination of mayors over city councils is being observed, although the latter is a local government body. The strong position of mayors as executive bodies in city councils precisely demonstrates the structurally embedded model of administrative funding and development of municipalities.

We could talk about power parity between city councils and mayors in a streamlined version where local governments impose taxes on the local population and they do not depend on any outside subsidies and grants. The alternative that increases the dependence of municipal budgets on the efficiency of local administration under the governance of mayors (utilisation of subsidies and grants) more than the dependence of local budgets on city councils (own revenues) implies the strong position of mayors by definition and neglects the local governments’ roles.

The fact that local governments perform administrative functions only – utilising and expending funds, separating them from local economies and the lack of opportunities for implementing policies – negates the essence of the political process, and constitute the main prerequisites for the malfunctioning democracy on local level. The underlying principle of modern democracy that sets the relation between representation and taxation (reallocation of public funds) has been seriously disrupted on local level. And the point of this principle is people, as being taxed, to get a representation in the government; there is such a representation in Bulgaria, in the instance of local government, but this representation does not have so serious influence on local finances. Municipalities in reality can largely function without any need of city councils (i.e. without complying with the principle of representation), because adopting their budgets is largely an administrative process (though formally voted by local governments), not a political one.

In addition to the governing role of mayors in respect of city councils, the phenomenon of ‘mayor and entrepreneur’ has been increasingly developing in Bulgaria. The leading role of mayors is distinguishable in both the political life of municipalities and local economies. The administrative development of districts largely favours this phenomenon, which shows once again that this matter is not a financial one – whether there is money for districts – but a structural one – how are local budgets structured and what incentives they offer to the administration. It is structural matters that are the main cause to look for an alternative to high political dependence of municipalities and swapping the political process for an administrative one.

Possible tax changes regarding municipalities

A real change in respect of financial independence of municipalities is possible only via restructuring the taxation system in Bulgaria. Imposing new taxes (on turnovers or on investments made) would constitute an economically untenable and highly myopic decision. The state already taxes profits, incomes, properties, transactions and consumption, i.e. any new tax would mean double taxation of any existing item. The only possible solution would be restructuring the existing tax system.

Decentralisation of indirect taxation, i.e. of consumption, also looks inapplicable in the current environment. VAT taxation does not imply the possibility of varying rates in individual districts because that would cause a real chaos along the chain and a huge administrative burden for both the tax authorities and companies. The high fragmentation of municipalities in Bulgaria means that it would be too easy to search for some kind of a ‘tax arbitrage’ by artificially directing consumption to municipalities imposing lower tax rates.

Even if a technical solution is to be searched for, i.e. all to be equally charged but a certain part of VAT revenues to be allocated back to municipalities, again it is highly disputable if the contribution of each municipality in the total VAT revenues could be assessed (there are also the so called ‘large taxpayers’). As at the moment, this option seems almost inapplicable, and it does not provide for alternatives for upgrading, i.e. the limit is administrative allocation of revenues without any real tax powers and varying rates in the future.

So, we come to the most likely scenario, namely decentralisation of direct taxes, in other words, taxation on profits and incomes. Taxing profits is an enticing option because it automatically binds local revenues with economic activities, entrepreneurship, investments and profits, but faces some insurmountable administrative and logical obstacles. Big companies again constitute a problem because they operate in many districts or even throughout Bulgaria, but pay corporate income tax in the municipality where they have their registered office. It seems almost impossible to estimate what proportion of the profit was generated in individual municipalities, and how to allocate tax revenues respectively. An incentive for tax arbitrage and artificial registration of companies – despite performing business activities elsewhere – in low-tax municipalities could arise again in the long run if municipalities are allowed tax powers and abilities to impose varying corporate income taxes. In other words, such a decision would not be quite appropriate in terms of regional development and the competition between local authorities.

The most reasonable and applicable scenario would be a change in respect of the income tax. Such an option would mostly fill in the notion of the relation between representation and taxation – local authorities would get a portion from taxing local citizens’ incomes. The specified change automatically makes local budgets dependent on employment rates and salaries (including the share of the informal economy in the so called employment relations) in districts, which sets the proper incentives – attracting foreign investors and removing hindrances to businesses would entail a direct financial result for municipalities. Such a change sets the prerequisites for tax competition between municipalities, and not via the tax arbitrage specified above, but rather via real competition that presupposes the so called ‘foot voting’ and changing domiciles due to tax considerations.

Municipalities and income taxes

A possible change in respect of income taxes, in purely theoretical terms, would provide solutions to the specified structural problems that local finances face. Firstly, even a slight change could seriously affect local budgets: the allocation of 20% of income taxes would in reality mean funds amounting to more than 500 million BGN, i.e. more than the regional programme specified above. Next, such a change would respond to fundamental economic and political questions: it would create incentives for municipalities to work on creating more jobs and on stimulating businesses to pay higher salaries, and it would recover the relation between representation and taxation. Such a change would provide prerequisites for tax competition without any artificial tax arbitrage. Finally, the changes are politically and administratively achievable. What options are possible and what could be undertaken as soon as possible?

In the short run, such a change in taxes could affect the allocation of funds towards municipalities – the tax rate is to remain the same in the entire country while portions of it are to be allocated automatically to the respective municipalities. Equal sharing of income tax revenues between the state and municipalities could be considered in the long run; even, it could be entirely transferred to local authorities. And since the last two options require normative and administrative amendments (which makes them longer term in their nature), the first one – with reallocation of revenues – could be implemented as early as next year.

No administrative amendments in tax authorities, which could continue to work in the same way, are necessary in order to provide for such a reallocation. The main point here is not the mere collection of revenues, but the subsequent reallocation of a portion of these revenues to municipalities. For the subsequent reallocation of these revenues, it is necessary to estimate the number of persons residing in a municipality and, also, to relate income taxes paid by every individual to the relevant municipality. These are the only administrative prerequisites.

In respect of the distribution of the population per municipality there is an easy solution, namely to be performed as per permanent addresses, i.e. as per identity cards. This is the most appropriate theoretical solution – one pays their taxes where, at least officially, they live. This is the most appropriate solution from a practical point of view because the correlation between taxation and representation will be recovered to the fullest – one pays their taxes where they vote for a mayor and councillors. The main point here is not the location of generating revenues (keeping in mind the daily occupational migration, for example), but rather the taxpayers’ locations of residence and voting.

By reason of the unsettled matters pertaining to the address registration of the population and by reason of the fact that many people live and work in the economic centres, though they still officially are domiciled in any of the smaller settlements, it could be stated that such a division by ID cards would affect unjust taxation in relation to towns and cities that would lose revenues (like the capital city). This approach makes a similar division imperfect, but it still remains the best one possible. Moreover, it allows taxpayers to decide where a portion of their income tax is to be allocated. As at the moment, one of the reasons for the chaos with regard to address registrations is the lack of real incentives that would urge people to register in municipalities where they really live and intend to stay. Such a tax amendment would provide an incentive and everyone could decide where their tax should go and which municipality to support – whether to keep their registered address in the hometown (village), or to renew their ID card and to support the municipality of their new home.

Practically, the implementation of the ‘money follows the ID card’ principle could help to solve the problem with registered addresses in Bulgaria. This principle is the most appropriate one also due to the fact that a very limited number of employees submit tax returns, where various options could possibly be implemented for the allocation of taxes paid to municipalities. Income taxation mostly concerns employees, i.e. people whose taxes are being submitted by employers. This is why an internal administrative decision, like the one regarding the ‘money follows the ID card’ principle, should be sought; such a decision should be implemented immediately without any activities on behalf of the taxpayer. A prerequisite for the implementation of this principle is certain administrative changes to be made because the tax administration cannot currently allocate income tax revenues to the respective municipalities. Finding a connection between the tax administration’s records (paid income taxes against every National ID No.) and the ones of the ESGRAON System (permanent address against every National ID No.) would be achievable within short terms.

From a financial point of view, the first step could be the reallocation of two percentage points or 20% of the income tax towards municipalities, which would provide funds bigger than the so called ‘regional programme’ and more than 10% of local budgets. It could be possible to enforce a term regarding the first two or three years following the change, stipulating that the revenues from the allocated income taxes to be solely used for investments and reimbursing old debts, in other words, to undergo a period of enhancing local finances. Such a measure, made under the specified restricting terms, would minimise risks, and it could pave the way for further decentralisation that would include either sharing income taxation or the entire transferring thereof to municipalities.

Conclusion

Challenges before local finances in Bulgaria do not arise more due to the lack of resources than the intense dependency of local budgets on state finances and EU funds. The structure of local budgets do not contain incentives for attracting foreign investments or for removing hindrances before local entrepreneurs; it entirely focuses on the utilization of EU funds in their capacity as the sole alternative for the inflow of funds in municipalities and for funding public projects. Moreover, the creation of a centralised programme for investments in districts makes regional development dependent on political rivalries, and only aggravates the structural problems before local finances.

The lack of financial independence of municipalities causes democratic problems by discontinuing the connection between taxation and representation on local level, it neglects the financial role of the local parliament, and implies a purely administrative budget process locally. A change both in economic and financial incentives and also in the relation between the representation on a local level and local budgets is possible only by means of restructuring direct taxes, and in particular the income tax.

We specified a short-term option for the reallocation of two percentage points or one fifth of income tax revenues for municipalities without any change in the national tax rate, by complying to the ‘money follows the ID card’ principle. The reallocation should be automatic and as per the permanent address of the taxpayer. The adoption of a transitive period of time is also possible, where the reallocated funds should be expended only on local investments or on repaying old debt – a period of enhancing local finances. In the medium and long term, either sharing the income tax revenues between the state and municipalities, or the complete reallocation thereof to local authorities, could be considered.

[1] Check the series of articles of the IME regarding this topic: on possible alternative (’How to Invest in the Regions?’, November 2013), on gaps and risks in the programme (‘How to Spend 500 m BGN?’, January 2014) and on empirical evidence that money has been spent with political motives (‘Money for the Regions – Transparently and to Our People’, February 2014).

Latest news

Math talents on the edge of the map 30.06.2025

If you think that mathematics can only be taught and learned well in mathematics high schools or elite...

The municipalities need more own resources and a share of revenues from personal income taxation 26.06.2025

IME analysis shows opportunities for expanding municipalities' financial autonomy. The budget expenditures...